Abstract: The growing use of new technologies has contributed to the rising interest in, and the changing approaches to, military procurement. The dominant explanation for this growing interest is the method of providing services. The changes in the Azerbaijani strategic approach used in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict in 2020, served as a critical mechanism for Azerbaijan’s success. A literature review, expert survey, and expert interview were conducted to analyse the change in approach. This paper suggests that a new political and strategic “business model” called “all-inclusive” was used to deliver military services to Azerbaijan by Turkey. Therefore, what was observed may be the end of traditional procurement in the military sector.

Bottom-line-up-front: Victory in the 2020 war, was ensured due to Azerbaijani technological superiority over Armenia. Additionally, the speed of the outbreak of hostilities introduced an element of unpredictability. Thus, with the end of the traditional procurement route, experts in the military sector may have lost their familiar, predictable procurement environment.

Problem statement: How did the adoption of this new “all-inclusive” service influence the conduct of warfare in the 2020 war in Nagorny Karabakh?

So what?: The Nagorny Karabakh war of 2020 showed that with traditional procurement, what war would be in 2021. Governments need to be aware of and prepare for procurement programmes that consider the changes in modern procurement systems to prevent failure in armed conflicts in the future. Furthermore, small states need to analyse their enemies’ procurement activities and the allies of the enemies.

Source: shutterstock.com/Photographer RM

Technology as the Game Changer?

The Oxford researcher Miles Brundage states in his 2018 co-authored work The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation that the growing use of artificial intelligence (AI) will lead to highly effective, finely targeted attacks.[1] AI is a technology that changes the “face of war”, as evidenced by the 2020 war between Armenia and Azerbaijan, where the Azerbaijani army used conventional drones equipped with AI.

The conflict over the Nagorny Karabakh (NK) region saw the Azerbaijani army use smart drones. With the end of the conflict, Azerbaijan’s army was victorious. It recaptured key portions of NK and forced Armenia to withdraw from areas it had held for twenty-six years. This achievement was made possible because Azerbaijan, armed with high-tech unmanned aerial systems—i.e., Turkish, and Israeli drones— was able to amass a series of impressive victories and destroy the Soviet-era tanks and equipment of the Armenian army. The proliferation of drones proved pivotal, leaving Armenia—who previously defeated Azerbaijan in 1994 in the same region —with few viable military options.

Heavy use of modern missiles, drones, and rocket artillery have been documented throughout the NK conflict.[2] Even if Armenia and Azerbaijan had invested in modernizing their militaries, Azerbaijan was considered a more diverse and qualitatively superior force. Armenia’s missile arsenal was mainly from Russia, consisting mainly of Tochka and Scud missiles of the former Soviet Union, as well as Russian Iskander missiles. According to the Centre for Strategic and International Studies experts Shaan Shaikh and Wes Rumbaugh, Armenia’s unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) fleet consisted of smaller indigenous systems focused on reconnaissance missions and, therefore, recognized as less capable than Azerbaijan’s fleet of foreign UAVs.[3] Azerbaijan inherited Tochka missiles from the Soviet Union; purchased Israeli LORA ballistic missiles and EXTRA (EXTended Range Artillery) guided rockets. These proved to be more accurate than the older Soviet missiles. Azerbaijan also developed an impressive drone arsenal composed of Turkish Bayraktar TB2 and Israeli Harop.[4], [5]

Even if Armenia and Azerbaijan had invested in modernizing their militaries, Azerbaijan was considered a more diverse and qualitatively superior force. Armenia’s missile arsenal was mainly from Russia, consisting mainly of Tochka and Scud missiles of the former Soviet Union, as well as Russian Iskander missiles.

According to the survey of experts consulted for this research: (1) drones used by Azerbaijan in the NK conflict are remote-controlled weapons; (2) the Azerbaijanis widely and effectively used their UAV arsenal; (3) the Russian electronic jamming systems used by the Armenians proved ineffective against Azerbaijani UAVs.[6]

Based on particular recent reports, drone warfare has received too much attention in the NK conflict.[7], [8] Such attention is especially true for Azerbaijani drones, which were the centre of attention in evaluating the war. These weapons are considered game-changing because they provide intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, and long-range strike advantages.[3] In this conflict, UAVs were integrated with fires from aircraft and artillery. However, it is possible to ask if the role of drones in this conflict was exaggerated? The military cannot, in practice, ignore this technology, of course. But behind Azerbaijan’s military operation, the use of modern technology was underwritten by systemic planning.

Sharpening the Yatagan: Military Capability Demonstrated in Nagorny Karabakh

New technologies are not valuable if they are not used in conjunction with a conceptual approach.[9] An approach may involve updating assets (replacing manned strike aircraft with UAVs) without applying the updated concept, reducing the new technology’s overall effect and not leading to significant military innovations. True advancement may be the result of conceptual and organizational changes. Therefore, the use of UAVs cannot be identified as the future of war. The socio-political context is also essential in influencing strategic actions and military innovations.[10] Possession of military capability can lead to their use. However, this is not necessarily true in all cases. The use of force depends on various indicators (budget, equipment, etc.). Also, opportunity and willingness influence the decisions to use force.[11] The Turkish arms industry of today has demonstrated in NK the end-product of a multifaceted, long-term process marked by – (i) constant investments in domestic (Turkish) defence industries, with Turkish lessons learnt, for instance, from each Syria campaign, and cooperation with other countries to improve the defence industry; and (ii) building Azerbaijan’s armed forces after the collapse of the Soviet Union through training, education, institutional development.[12], [13]

True advancement may be the result of conceptual and organizational changes. Therefore, the use of UAVs cannot be identified as the future of war.

In the 2020 war, the concept of Network-Centric Warfare (NCW) was essential to the Turkish-Azerbaijani military plan. The NCW was based on the Soviet reconnaissance-strike (strategic/operational level) and reconnaissance-fire (tactical level) complex.[10] This complex was adjusted and detailed with new concepts as new technologies appeared. Such adjustments included integrating precision weapons systems, intelligence, command, and control systems to quickly assess the situation, definition of targets and distribution of tasks. The concept of NCW places great emphasis on intelligence: the gathering and analysing information using automated systems to deliver high-precision strikes over long distances.[14] Based on the idea of NCW, the Joint Vision 2020 concept was developed in which the military strategy of full-spectrum dominance was presented.[15] The strategy implied achievement of superiority in the military domain: from peacekeeping through to the direct use of military force, all of which would be founded on the achievement of information superiority. This was observable in the Turkish-Azerbaijani approach to returning the occupied territories and in the final act of the war when Russia secured a truce.

It was evident during the NK conflict that UAVs can be considered central to the NCW concept. One could observe that critical elements of the Turkish-Azerbaijani model of operations were strengthened due to the use of UAVs and the integration into a network on the principles of the NCW. According to the expert survey, it is possible to use drones in two different but complementary approaches to military operations: (i) to hit targets, avoiding direct use of troops; (ii) use of suicide drones to destroy enemy air defences. These complement each other since the reason for using a drone is the same in both cases: the desire to limit risk to humans.

Turkey’s military operations are characterized by the ease and efficiency of transferring the expeditionary model from one context to another (for instance, using drones in Afrin, Libya). According to Vincent Tourret of the Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, Turkey participates in models of the “alternative Revolution in Military Affairs” (ARMA). However, Turkey is more interested in technical solutions of modernization of forces and industrial power than military issues’ doctrinal development. The “hyper-technological” American ARMA model has compelled other states to develop counter-models to bypass American strengths by using asymmetric methods. The models seek to combine (i) a popular mass rally, (ii) political subversion, and (iii) unsophisticated technologies, adapted to the two previous elements, (iv) and to integrate technology with non-regular forces.[6]

However, Turkey is more interested in technical solutions of modernization of forces and industrial power than military issues’ doctrinal development.

Analysing the theatres of Turkish military operations since the 1990s, Tourret concludes that Turkish doctrine was based on NATO’s Follow-On Forces Attack (FOFA) concept, based on the old European concept of the “fire belt”.[6] Until 2010, a strategy was developed with an emphasis on the development of local reservists. In addition, the strategy notes the following successes: (1) the development of the domestic defence industry, which meets more than 75% of defence needs, (2) the use of tactical actions using UAVs to achieve strategic goals. Thus, Turkey is going through a period of experimenting with doctrines for “acquiring mobility and strategic perception within the framework of theories of network-centric warfare and impact-based operations”.[16] Tourret’s observations correlate with the opinion of Borchert et al. that “military innovation is a process, not a static outcome”. According to responses from Tourret for current research, “Turkish logic resembles FOFA and the “fire belt” in the sense that the country no longer intends to take refuge in the retreats of the Anatolian plateau. The strategy intends to develop an “advanced” defence outside the country. Turkey is thus trying to emulate FOFA by their emphasis on indirect fires, deep striking and networking of sensors and effectors”.[17]

Turkish logic resembles FOFA and the “fire belt” in the sense that the country no longer intends to take refuge in the retreats of the Anatolian plateau.

Tourret’s observations also correlate with the opinion of the expert survey participants: who agree that Azerbaijan has applied a combination of doctrines – Soviet ground attack tactics with innovations, especially with the extensive use of special forces, and a Western doctrine of the use of aviation, i.e., Azerbaijan combined the strengths of each of the doctrine.

According to the survey result, Baku applied the doctrine preferred by most NATO armies due to the influence of Turkey (a NATO member-state). This doctrine seeks air superiority guaranteed by air-to-air assets such as fighter jets and a continuous air campaign to suppress and destroy enemy air defences.[6] Azerbaijan used both ground and air assets at an early stage to destroy the Armenian air defence systems so that later it could attack Armenian ground assets.

In Russia, the fundamental basis of military strategy is the creating of a system for studying predictive scenarios for the outbreak and conduct of military conflicts.[18] Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) the newspaper of the armed forces of Russia wrote that Russia developed a strategy of limited actions aimed at protecting and promoting national interests outside the country.[19] The basis for its implementation is the creation of a self-sufficient grouping of forces based on formations of one of the branches of the Russian Armed Forces, which has high mobility and can make the most significant contribution to solving assigned tasks. According to Borchert et al., an innovation widely used by Russia in Ukraine in 2013-2015 was the battalion tactical group.[10] One of the most critical conditions for implementing this strategy is the transfer of hostilities to the information environment. Borchert et al. note that the military is increasingly dominated by “warstreaming”, that is, the ability of the opposing sides “to provide live feeds from the battlefield”. The security and defence expert Torben Schuetz indicated that “videos shown to the public and uploaded to social networks were curated and selected to construct the narrative of a “clean” victory [in the 2020 war]”.[6]

The Importance of Constant Procurement Analysis

According to Schuetz, one of Armenia’s main mistakes was the lack of crucial, constant analysis of Azerbaijan’s arms purchases and adequate domestic military procurement reactions.[20] The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute reports in its 2017 yearbook that there can be limitations: lack of data or availability of inaccurate data.[21] One of the expert survey participants supported this by noting that (i) a few states publicly record the criteria of their weapons that comply with Art. 36 of the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I) of 8 June 1977 and (ii) based on national security considerations, none of the states publish weapon reviews.

Armenia also missed cultural-political factors that would have helped compensate for incomplete data. In developing states, procurement decisions could be predetermined by cultural and political factors, making the tender result predictable.[22] Hence, considering the “force of gravity” between Baku and Ankara, Yerevan could have analysed the Turkish military industry and theatres of military operations in Syria and Libya.

The German Marshall Fund contributor Haldun Yalcinkaya mentions the “One Nation, Two States” principle used by Azerbaijan and Turkey, which positively influenced the rapprochement of the two states.[12] However, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, such rapprochement was not easy due to (i) changes of heads of executive power in Azerbaijan during 1992-1993 and (ii) the attempt of Turkey to normalise the relationship between Turkey and Armenia, which Azerbaijan negatively received.[23] Nevertheless, Turkey constantly invested in building the Azerbaijani military escaped Armenia’s notice. According to Professor Taras Kuzio of the National University of Kyiv, Turkey uses the same “One Nation, Two States” principle towards Crimean Tatars.[24] Therefore, what is essential for Russia, for instance – is not to rely solely on its veto power but to profoundly scrutinize the military procurement of Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Nevertheless, Turkey constantly invested in building the Azerbaijani military escaped Armenia’s notice.

“All-Inclusive” Service

The discussion above was commented on by another interviewee, according to whom: Armenia expected a repeat of the 2016 scenario. However, although procurement analysis is useful, it would not have helped in this case because the procurement outline takes time from defining the military requirement to “final delivery of the product”. Azerbaijan nominally procured the first Bayraktar drones from Turkey in July-August 2020, and since it takes time to train pilots, these drones were flown by Turkish pilots. Thus, in essence, Azerbaijan procured the weapon systems and employed them immediately. This was thanks to its access to petrodollars and Turkish military experts and equipment. If Armenia had realized that Azerbaijan was buying a brand-new weapon system, it would have estimated that Azerbaijan would have a few operational drones by 2021 when analysed with traditional procurement analysis. Instead, the drones bought in July-August were used in September. This rapid turnaround was down to the fact that it was not a normal procurement by Azerbaijan but rather direct military assistance from Turkey. Therefore, what was observed is an “all-inclusive” service or package purchased by Azerbaijan.

If Armenia had realized that Azerbaijan was buying a brand-new weapon system, it would have estimated that Azerbaijan would have a few operational drones by 2021 when analysed with traditional procurement analysis. Instead, the drones bought in July-August were used in September.

Azerbaijan has been buying more weapons from Turkey and Israel than Russia in recent years, accounting for only 22%[25]. Armenia without significant funds has been forced to rely on the capabilities of their defence industry. In addition, the air-defence system of NK is less capable than the Armenian one. It consisted of rather old complexes, it did not have a solid radar field, and therefore drones operated there “with impunity” because NK did not have funds to purchase modern air defences and electronic warfare systems capable of fighting drones.[26]

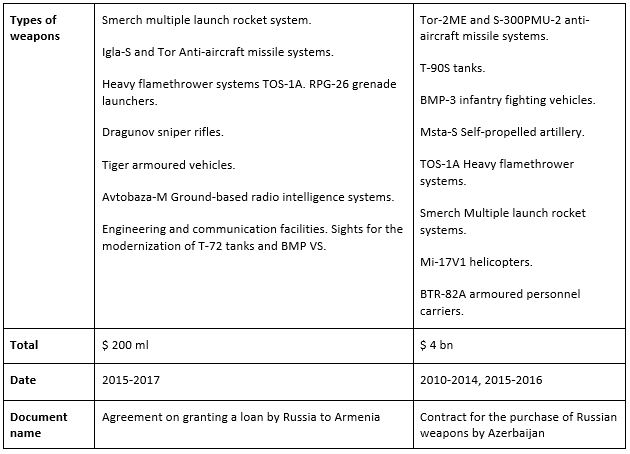

Russia has provided arms to the Armenian military in recent years. However, it has also supplied arms to Azerbaijan. A breakdown of these systems is available in the table below:

Table A – Russian arms purchases by Armenia and Azerbaijan

In percentage terms, in 2019, the costs of arms imports to Armenia amounted to 4.9% of the share of GDP, Azerbaijan – 3.9%. The costs amounted to $652 million in Armenia and $1854,2 million in Azerbaijan. One of the interviewees stated that it is possible to win a war, even with low economic performance, which was countered by another interviewee who underlined that this is possible relative only to small conflicts. Brundage et al. state that the decreasing cost of equipment (drones, for example) increases the probability of its use by various actors, thus increasing the probability of new attacks.[1]

Conclusion

The technologies of Turkish and Israeli origin used in the 2020 war in NK are associated with the automation of targeting and attacking functions. Such features made these weapons a relatively low-cost yet significant threat to Armenia, which did not possess them. The Turkish-Azerbaijani military plan in NK was based on Soviet and American origin doctrines adopted by Turkish experts considering modern technologies.

With constant monitoring and procurement analysis of Azerbaijan and Turkey, Armenia would not have much chance because traditional procurement analysis is no longer relevant since states can purchase “all-inclusive” packages. The survey experts believe that Azerbaijan was much better prepared for the war than its enemy because its spending on weapons was more meaningful than Armenia, and its planning was more thorough. With the “all-inclusive” package purchase, Azerbaijan saved time and effort on studying the experience of war in the Middle East since Turkey carried out all this work. According to Borchert et al., there is a new trend, called “War as a Service” – a modern political and strategic business model that stimulates military power transfer on a government-to-government basis.[27] For the current case study, the term “all-inclusive” was used because it included a package of services delivered by Turkey, to which Azerbaijan owes the victory and for which it certainly paid.

With the “all-inclusive” package purchase, Azerbaijan saved time and effort on studying the experience of war in the Middle East since Turkey carried out all this work.

Botakoz Kazbek; is a graduate of the University of Padua and the University of Grenoble Alpes double degree programme, with more than ten years of professional experience. She has received degrees in Human Rights, Finance and Banking, and International Economics from Italian, French, Kazakh and Polish universities. Her research interests centre on human rights, public administration, security studies, and peacekeeping. She is the author of “Existing powers and alliances before the 2020 war in Nagorny Karabakh” (International Institute for Global Analysis, 2021). The views contained in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of the University of Padua, or the University of Grenoble Alpes, or the Catholic University of Lyon.

[1] Miles Brundage, Shahar Avin, Jack Clark, Helen Toner, et al., The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation (University of Oxford, University of Cambridge, Center for a New American Security, 2018), Electronic Frontier Foundation, OpenAI, 11, retrieved from https://www.eff.org/files/2018/02/20/malicious_ai_report_final.pdf .

[2] David Barno, Nora Bensahel, “War in the fourth industrial revolution,” War on the Rocks, vol. 19 (2018), retrieved from https://warontherocks.com/2018/06/war-in-the-fourth-industrial-revolution/.

[3] Shaan Shaikh, Wes Rumbaugh, “The Air and Missile War in Nagorno-Karabakh: Lessons for the Future of Strike and Defense,” 2020, 12 8, last accessed May 26, 2021, https://www.csis.org/analysis/air-and-missile-war-nagorno-karabakh-lessons-future-strike-and-defense.

[4] Seth Frantzman, “Did Azerbaijan’s use of Israeli weapons make the war worse or better?,” 2021, 03, retrieved from https://www.jpost.com/international/did-azerbaijans-use-of-israeli-weapons-make-the-war-worse-or-better-662442.

[5] Sabah Daily, “Turkish, Israeli made drones gave Azerbaijan upper hand, German media argues,” 2020, 11, retrieved from https://www.dailysabah.com/business/defense/turkish-israeli-made-drones-gave-azerbaijan-upper-hand-german-media-argues.

[6] Botakoz Kazbek, Artificial Intelligence in Warfare: The Influence of Using Autonomous Weapon Systems on The Balance of Power in High Karabakh (University of Grenoble Alpes, University of Padua, Catholic University of Lyon, 2021), 07.

[7] “The Azerbaijan-Armenia conflict hints at the future of war,” The Economist, 2020, 12 8, retrieved from https://www.economist.com/europe/2020/10/08/the-azerbaijan-armenia-conflict-hints-at-the-future-of-war.

[8] Can Kasapoglu, “Turkey Transfers Drone Warfare Capacity to Its Ally Azerbaijan,” 2020, 10 15, retrieved from https://jamestown.org/program/turkey-transfers-drone-warfare-capacity-to-its-ally-azerbaijan/.

[9] A Yatagan is a short Ottoman Sabre that retains a historical and cultural significance in Turkey.

[10] Heiko Borchert , Torben Schutz, Joseph Verbovszky, „Beware the Hype. What Military Conflicts in Ukraine, Syria, Libya, and Nagorno-Karabakh (Don’t) Tell Us About the Future of War,” Defense AI Observatory, 2021, retrieved May 2021, from https://defenseai.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/DAIO_Beware_the_Hype.pdf.

[11] Benjamin Fordham Benjamin, “A Very Sharp Sword: The Influence of Military Capability on American Decisions to Use Force,” The Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 48, No. 5, 2004 (10), 632-656, retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4149813.

[12] Haldun Yalcinkaya, “Turkey’s Overlooked Role in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War,” The German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2021 (01), retrieved on October 01, 2021, from https://www.gmfus.org/news/turkeys-overlooked-role-second-nagorno-karabakh-war.

[13] Ali Balci, Cahit Celik, “Turkey’s Military Power in the 2000s: an Assessment for Measurement Methods,” Turkish Policy Quarterly, 2019 (08), retrieved on October 01, 2021, from http://turkishpolicy.com/article/973/turkeys-military-power-in-the-2000s-an-assessment-for-measurement-methods.

[14] David Alberts, John Garstka, Frederick Stein, “Network Centric Warfare: Developing and Leveraging Information Superiority,” CCRP publication series, 2020, 2nd Edition, retrieved from http://www.dodccrp.org/files/Alberts_NCW.pdf.

[15] Joint Chiefs of Staffs, Joint Vision 2020: America’s Military: Preparing for Tomorrow, 2000 (06), retrieved on May 23, 2021, from Homeland Security Digital Library: https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=446826.

[16] Vincent Tourret, “La stratégie aéroterrestre turque en quête d’une doctrine nationale,” Areion News, June 08, 2021, https://www.areion24.news/2021/06/08/la-strategie-aeroterrestre-turque-en-quete-dune-doctrine-nationale/.

[17] Vincent Tourret to Botakoz Kazbek, Emails dated October 25, 2021, and October 27, 2021.

[18] Valery Gerasimov, Report of the First Deputy Minister of Defense of Russia, 2019 (07 03), retrieved on May 23, 2021, http://csef.ru/en/oborona-i-bezopasnost/348/vektory-razvitiya-voennoj-strategii-8829.

[19] Krasnaya Zvezda, Gazeta Vooruzhennyh Sil Rossiiskoi Federacii (2019, 03), Vektor Razvitiia Voennoi Strategii. retrieved from http://redstar.ru/vektory-razvitiya-voennoj-strategii/.

[20] Torben Schutz to Botakoz Kazbek, Email dated November 11, 2021.

[21] Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Yearbook 2017, “Armaments, Disarmaments and International Security,” Chapter 9, Military Expenditure, retrieved from https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2017.

[22] Caglar Kurc, The Role of Culture and Politics in Arms Procurement, The Sixteenth Annual International Conference on Economics and Security, Middle East Technical University, retrieved on June 01, 2021, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235258532_The_Role_of_Culture_and_Politics_in_Arms_Procurement.

[23] Konstantin Yumatov, Ksenia Sivina, “Azerbaijano-tureckoe vzaimodeistvie v kontekste mezhdunarodnyh otnoshenii na Uzhnom Kavkaze (1992-2020 gg.). Vestnik Kemerovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta,” Vol. 22 (4), 2020 (12), 963-971. Doi: 10.21603/2078-8975-2020-22-4-963-971.

[24] Taras Kuzio, Turkey Forges a New Geo-Strategies Axis from Azerbaijan to Ukraine, 2020 (11), retrieved on October 01, 2021, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/turkey-forges-new-geo-strategic-axis-azerbaijan-ukraine.

[25] Sergei Valchenko, “Ocenen eksport rossiyskogo oruzhiya v armeniyu i azerbaydzhan,” Moskovskii komsomolec, October 16, 2020, retrieved from https://www.mk.ru/politics/2020/10/16/ocenen-eksport-rossiyskogo-oruzhiya-v-armeniyu-i-azerbaydzhan.html.

[26] Pavel Aksenov, “Voina dronov v Karabahe: kak bespilotniki izmenili konflikt mezhdu Azerbaijanom i Armeniei,” October 06, 2020, retrieved on June 2, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/russian/features-54431129.

[27] Heiko Borchert , Torben Schutz, Joseph Verbovszky, „Beware the Hype,” 7.